By Dr Martin Forde, Sc.D., R.Eng

While the mosquito-borne virus named Zika has yet to be officially identified in Grenada and most of the other English-speaking Caribbean islands, it has already started to impact the region.

Instead of waiting for the beginning of the week, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), took the very unusual step this past Friday (15 January) of issuing a warning to pregnant women against travelling to 14 Latin American and Caribbean countries. The reason? Given growing evidence that Zika can cause serious brain damage to unborn babies, CDC felt they had to get this travel advisory warning out as soon as possible rather than wait till the start of the next week.

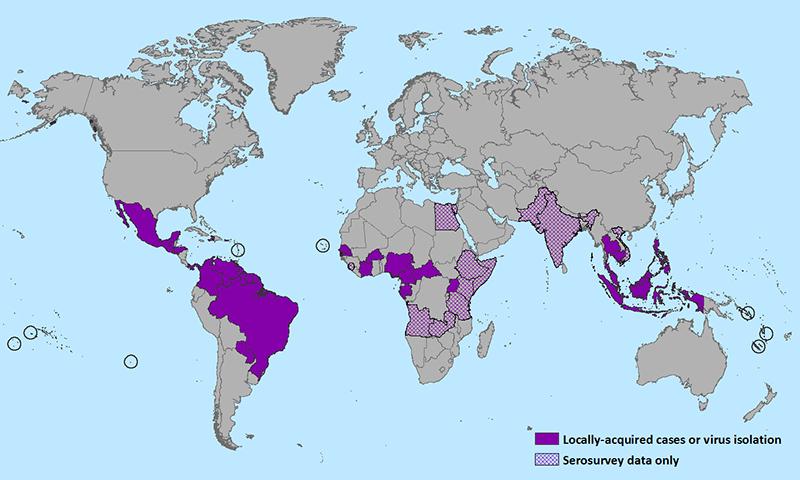

Like Chikungunya, Zika was first identifying in Africa — Uganda specifically — in 1947 and since then has steadily spread to other countries on other continents. The virus made its first major appearance in the Western Hemisphere last May 2015, when a large outbreak occurred in Brazil, which is still ongoing.

Until now, almost no one in the Western Hemisphere has been exposed to the Zika virus. As a result, very few persons have had their immune systems primed to recognize and then fight this virus. Such an immunologically naïve population provides the ideal setting for Zika to rapidly spread to many, many, persons. Now, just 8 months later, the one Zika infected country has mushroomed to 14 infected countries including such Latin American countries as Colombia, Venezuela, and Suriname. All these countries have experienced what those in public health call an outbreak.

Not surprisingly, the neighbouring Caribbean region has not been spared. To date, Zika cases have already been identified in Puerto Rico, Haiti, and Martinique. And just like Chikungunya which spreads like a wildfire after entering the Caribbean island of St Martin, it only seems reasonable to predict that Zika will likewise sweep through our beautiful islands in the weeks and months to come.

Given that Zika’s arrival in Grenada and other Caribbean islands is just a matter of time, a key question that arises is what are we doing now to prepare for its arrival and how best we can mitigate its effects. In a déjà vu way, this was the same question posed when we awaited the imminent arrival of Chikungunya. The first cases of Chikungunya were documented in Saint Martin in December 2013. Seven months later, the first Chikungunya cases were identified in Grenada.

While being infected by the Zika virus has been associated with relatively mild symptoms (one may think of Zika being like Chikungunya Lite), recent evidence seems to point to a special danger posed to the unborn child of pregnant women. Mounting evidence suggests that if a pregnant woman gets infected with the Zika virus, particularly during her first trimester of pregnancy, the risk of her child being born with a serious head and brain defect called microcephaly is greatly increased.

Although Zika has not ‘officially’ been identified within our shores, its impact is already been felt. As evidenced by the CDC’s recent travel advisory warning, persons are now being warned of the potential dangers of coming to the Caribbean. This is certain to have a material impact on the region’s tourism industry.

As is the case with most other Caribbean countries, Grenada heavily depends on the tourism industry to prop up its very fragile and vulnerable economy. As CDC’s travel advisory warning spreads to tour operators, airlines, and cruise ship lines, one wonders just how many might now choose to cancel that dream vacation to the Caribbean and take it somewhere else.

While it is not feasible for those currently Zika-free Caribbean countries to think that they can build a Trump-like Zika Wall, this does not mean that they should do nothing but just grimly await the unwelcome arrival of Zika to their shores.

If an attack is deemed imminent, beefing up one’s defences is always a prudent course of action to take. Thus, for Zika’s impending onslaught, one thing we could and should do now is review that status of our healthcare system and see how prepared it is to face such an assault.

Another thing we should do is check the status of our healthcare monitoring and surveillance systems. One cannot effectively battle and win a war with dodgy information. Our health care surveillance systems need to be strengthened and resourced, so that it can proactively monitor for persons who display the symptoms similar to those infected with the Zika virus, and then have the resources available to do rapid testing to confirm whether they are infected or not.

Thirdly, since Zika is a mosquito-borne infection, one does not have to wait for its arrival to start implementing mosquito control strategies. Keeping one’s surrounding as clean as possible and eliminating all possible mosquito breeding places will ensure that even if someone with Zika comes into our country, its ability to rapidly spread to others will be greatly reduced since there will be very few mosquitos around to do so.

Zika, while not (yet) officially making its entry into our island, has already started to exert an unwanted negative effect on our country, specifically our tourism industry. How big or damaging this effect will be only time will tell. Proactive, common sense, public health measures may nonetheless make Zika’s bite less painful and troubling, both to our health and our island’s economy.