by Felicia J Fricke, PhD

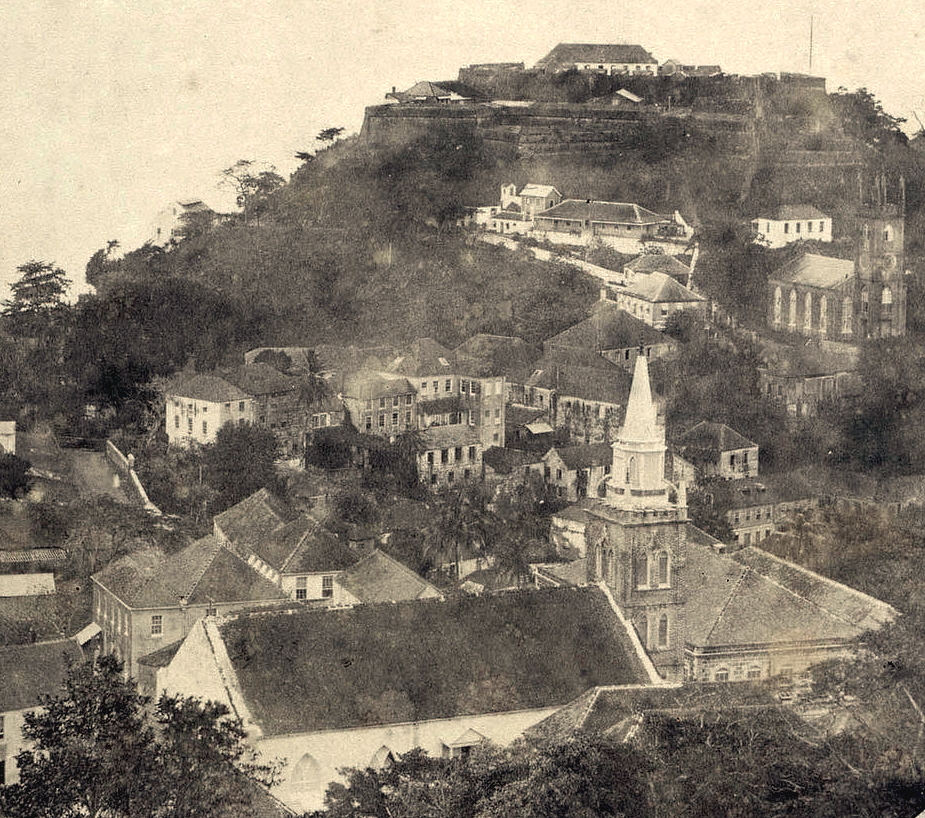

In 1828, young Irishman Antony O’Hannan arrived on Grenada to be the Roman Catholic rector. His close relationship with enslaved and free Catholics of colour made white Catholics and the colonial authorities rather anxious, and they attempted to get rid of him several times.

First, the Bishop in Trinidad tried to send him to Jamaica. Next, the Grenada Government revoked his licence to preach. However, O’Hannan remained, preaching illegally to his congregation. That he chose to stay was probably because he was so popular: the free Catholics of colour on the island organised numerous petitions that called for his official reinstatement as their pastor. Speaking both English and French, O’Hannan could effectively communicate with his largely French-speaking congregation. He also possessed a level of empathy for the enslaved people of Grenada that the government and the planters lacked. Using his own money, he set up several schools that catered to Catholic children, and he also served on the board of the Society of the Coloured Roman Catholics of Grenada.

As the Catholic and colonial authorities each tried to get rid of O’Hannan in their own ways, the local newspapers joined in by accusing him of starting a riot and of stealing from the church. By the summer of 1830, the atmosphere in Grenada was so tense that the Catholic powers and the British authorities decided to collaborate. This was remarkable considering the cultural, linguistic, and political differences that had often set these groups against each other. The Government Secretary began to compile evidence that could be used in a court case to try to prove that O’Hannan was a serious threat to the colonial order. The evidence consisted of rumours that stretched across the sea to Trinidad, St Barts, and Montserrat, and even as far as North America and Ireland. They passed between elite white Catholic men of different occupations and nationalities, who gave accounts that O’Hannan was guilty of rape, seduction, perjury, incitement to riot, and of causing the death of a bishop. Like many rumours, these accusations were designed to play upon existing fears and prejudices, namely the elites’ anxiety about revolt and their beliefs about the violence of Irish Catholics and the purity of white women.

However, the rumors, in this case, were ultimately unsuccessful in the goal of getting rid of O’Hannan. He stayed in Grenada and regained his licence to preach in 1832, possibly because the authorities thought his popularity might be useful in the precarious years just before the abolition of slavery. In 1840, O’Hannan passed away and was replaced by his good friend Samuel Power, who had also spent time on Trinidad supporting a revolutionary priest and man of colour named Francis de Ridder. These 3 men, O’Hannan, Power, and De Ridder, represent an important counterpoint in the history of Catholicism in the Caribbean. While the Catholic powers were often invested in upholding colonialism, there were some individuals who chose to interpret the church’s teachings differently and use them to strive for something else.

The O’Hannan story is recounted in a new open-access article by Dr Felicia Fricke in the New West Indian Guide. Dr Fricke is a researcher at the University of Copenhagen. She has been researching the history of Grenada’s rebel priest as part of her work in the history project IN THE SAME SEA. The project looks at connections between islands in the Lesser Antilles in the period from 1650 to 1850, and Dr Fricke found that the case of Grenada’s rebel priest was a particularly good example of inter-island connections among elite men.

She visited Grenada in March 2023 to assist the Grenada National Museum with the care of their collections. During her visit, she also gave a public lecture on her research findings at Norton Hall, St George’s. A Zoom recording of a similar lecture from December 2022 is available on YouTube and on the Facebook page of the Grenada Genealogical and Historical Society.