by John Angus Martin, A-Z of Grenada Heritage

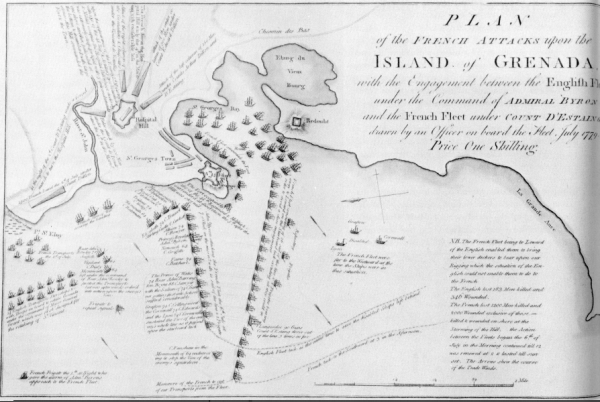

On this day, 6 July 1779, French naval forces, under the Comte d’Estaign, engaged the British under Vice-Admiral John Bryon off Grenada, forcing the retreat of the British, and bolstering the French control of Grenada.

Notified of the invading French force under d’Estaing, Admiral Byron and the British fleet arrived along the western coast of Grenada on the morning of 6 July. They were not sure what the situation was, but as they sailed down towards St George’s they saw what appeared to be a larger French fleet emerging from the Carenage. The British probably felt that they stood a chance of beating the French and retaining Grenada.

At about 7 or 8 am the two fleets engaged each other as the British fleet. The British had hoped to force the French “to a close engagement,” but they avoided that tactic. At around noon, the British found “it impossible to continue the engagement with any possibility of success, a general cessation of firing took place.” A second engagement began around 3 pm when the French fleet returned southward, forcing the British to resume the battle until sunset. As the fleets drifted apart the British retreated, their fleet badly damaged. According to Jamieson, Grenada was the most valuable colony after Jamaica and its loss to the French had been “the most serious blow to Britain since the American rebellion had been transformed into a global war.”

Official figures show that the British had 183 killed and 346 wounded, and the French had 190 killed and 759 wounded. The naval battle produced no winners, but the British had failed in retaking Grenada and forced to retreat, very badly damaged. The French couldn’t claim victory, however, though they could have had the upper hand had d’Estaing chosen to pursue Byron’s badly damaged fleet. Some historians concluded “that neither admiral distinguished himself.”

Celebrations in Paris, France

The news of d’Estaing’s victory over the British in the Caribbean led to celebrations in France. The French had demonstrated that the British did not control the seas as they had done during the Seven Years War. James Cornwallis, in a letter to William who had barely escaped as commander of the Lion, expressed the concern the Grenada capture had produced: “Admiral Barrington is come home in very ill-humour, and represents our situation in the West Indies as truly lamentable, where we thought ourselves strongest. Upon the whole, nothing can look worse than our affairs, although we have not yet had any great loss excepting Grenada, we are every day in apprehension of some bad news, How different from the last war, when we were only accustomed to victory.”

Louis-Antoine de Bougainville

Louis-Antoine de Bougainville (1729-1811), after whom Grenada’s national flower bougainvillea (Bougainvillea spectabilis) is named, took part in the capture of Grenada and the sea battle against the British in July 1779. He was the commander of the ship of the line Le Guerrier, which escaped comparatively unscathed and lost only nine men. The bougainvillea is a native plant of Brazil and was brought to France in 1768 by the explorer and botanist.